Robin Rogers was 35 weeks pregnant when she began to suffer from significant vomiting and dehydration. She was admitted to the hospital near her home in Kansas. To correct her fluid and nutrition levels, Robin had two tubes placed: one, a feeding tube; the other a PICC line, often used to draw blood or deliver antibiotics.

Robin Rogers was 35 weeks pregnant when she began to suffer from significant vomiting and dehydration. She was admitted to the hospital near her home in Kansas. To correct her fluid and nutrition levels, Robin had two tubes placed: one, a feeding tube; the other a PICC line, often used to draw blood or deliver antibiotics.

But when her tube feeding bag arrived on the hospital floor, there was a mistake.

The bag was hung to infuse into her PICC line, sending the feeding straight into her blood stream. By the next morning, Robin’s unborn daughter had died in utero. Two days later, Robin also died from the complications resulting from this “tubing misconnection.”

Tubing misconnections can be tragic, but they are not new. The first report of a tubing misconnection was in 1972. As with Robin’s story, these misconnections occur when fluids meant for feeding are mistakenly connected to an IV line. The root of the problem is that tubing connectors are compatible, increasing the likelihood that tubes and catheters that serve very different purposes can be connected incorrectly.

Making Tubing Connections Safe

By 2006, there were over 300 case reports of tubing misconnections across all age categories. That year the Joint Commission issued a Sentinel Event Alert on tubing misconnections’ safety risk to patients. The report called for updated manufacturing guidelines.

The Association for the Advancement of Medical Instrumentation followed in January 2011, adopting international design standards to reduce tubing misconnections among different types of devices. The standards encouraged manufacturers to reduce the risk to patients by creating proprietary connectors specific to their own devices. It also offered strategies for new designs. AAMI aimed to work with FDA and the International Organization for Standardization to have these standards fully implemented by 2014.

The guidelines’ complexity and the manufacturer requirements caused delays. But by 2014, the first prototypes of new syringe tips and connectors were introduced.

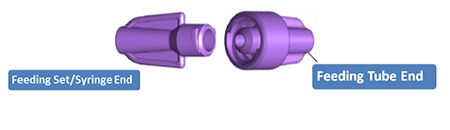

These were dubbed “ENFit.” The ENFit design minimizes potential errors by altering the design of tubing/ syringes to a “female” design to connect only with the “male” design of the feeding tube connectors.

Challenges for the Infant Population

But for the neonatal and pediatric populations, a design meant to reduce patient risks has instead introduced new challenges. Pediatric health care providers must deliver medicine in tiny volumes to our tiny patients, and we must do so with the highest levels of accuracy. The new connector design makes this difficult.

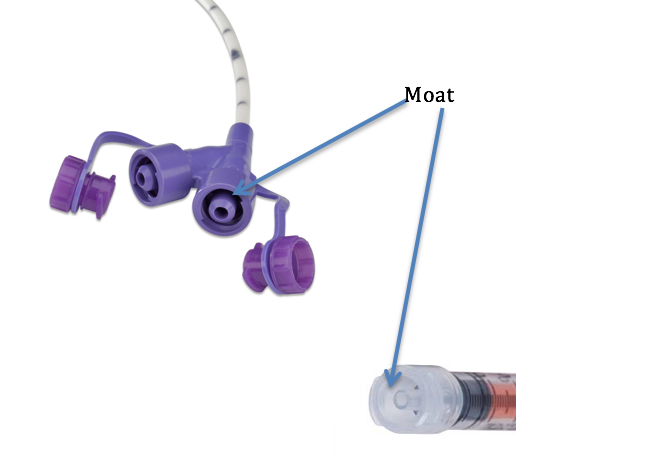

The moat, or area around the syringe barrel, is difficult to clear. Medication can “hide” there, inadvertently increasing the dosage delivered when the syringe is inserted into the feeding tube. If the moat is not cleared, a preemie may accidentally receive up to 30 percent more medication per dose. This places the baby at risk for overdosing and adverse drug reactions.

That leaves NICUs in a state of limbo. Medication safety experts and the pharmacy community are urging caution before hospitals adopt the ENFit design. While some hospitals hold off on adopting a product line, they must meanwhile ensure that all oral tubes and syringes are compatible both within their hospital and with any facility from which they receive or transfer patients.

The situation also poses workflow issues. Nursing staff face the added steps of regularly clearing syringe moats and feeding tubes. Pharmacy staff faces the new burden of providing oral solution adapters needed in drawing up medication doses.

Most concerning, the lack of a real solution leaves fragile patients at continued risk.

Improved standards mark an important step toward protecting patients like Robin and her unborn daughter from the dangers of tubing misconnection. But as we implement those standards, we must avoid mitigating existing risks by creating new ones. Otherwise, we fail to meet the needs of NICUs and, most importantly, the vulnerable patients they serve.

Suzanne Staebler, DNP, has been a Neonatal Nurse Practitioner for 25 years and currently practices in Atlanta, Georgia. She is a member of the National Coalition for Infant Health.