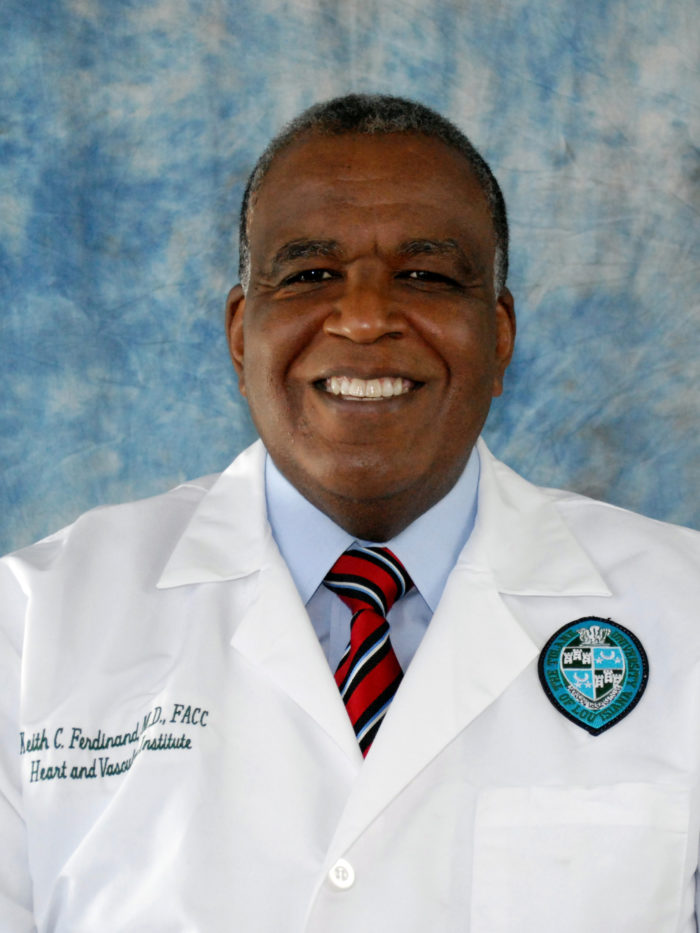

By Keith C. Ferdinand, MD

The toll of COVID-19 has hit the Black community with the power of a hurricane. I should know, because I was in New Orleans 15 years ago for Hurricane Katrina.

This time, the walls of New Orleans buildings are still intact, the streets free of debris. But inside homes, businesses and apartment buildings, the people of New Orleans – and all of Louisiana – are suffering higher unemployment rates and higher death rates than they did during the natural disaster. Black Louisianans bear the brunt of the pandemic’s damage, just as they did with Hurricane Katrina. More than half of the state’s COVID-19 deaths are Black residents, though they comprise less than a third of the state’s overall population.

New Orleans’ problems were far from over when the hurricane waters receded 15 years ago. It will be the same with the far-reaching impact of COVID-19. Not just New Orleans, not just Louisiana, but Black Americans across the country will feel this pandemic’s effects for years to come.

Certain factors make Black Americans less equipped to face these challenges. We know that Black Americans garner a lower household income than white families do, making it difficult to weather job loss and cover unforeseen shortfalls. Low socioeconomic status is linked with higher rates of cardiovascular risks such as diabetes, hypertension and obesity. The onset of cardiovascular disease is earlier for Black Americans.

And while the country’s population in general has seen a reduction in cardiovascular disease and death over the past few years, the Black community has not. Continued high cholesterol and hypertension mean that these men and women instead face ongoing and elevated risks of stroke, heart failure and heart attack.

Adding a pandemic to the equation does not bode well.

Experts predict a second wave of the novel coronavirus, potentially taking hold this fall. I foresee a third wave, not of COVID-19 itself, but of preventable medical complications and even deaths. Health issues are being pushed aside as Americans deal with economic woes or hunker down in their homes, afraid to seek medical care for chronic conditions.

For example, hospital visits for heart attacks and strokes have decreased during the country’s lockdown. Hospitals reported a 40% drop in severe heart attacks. Are people simply having fewer cardiovascular events? Or, more likely, are they attempting to ride out their symptoms at home? I fear some have taken stay-at-home orders to the extreme, and they may pay for the miscalculation with their lives.

In other cases, patients are losing touch with their health care providers and losing control of chronic conditions. Some patients are trying to direct their own care. Others are simply taking the gamble. They’re putting regular prescriptions and physician visits on hold while they tackle job loss, child care challenges, mounting expenses or caring for sick loved ones.

They will discover in the months ahead what their health care providers already know – cardiovascular risk doesn’t subside on its own. These conditions aren’t going away.

The medical community should prepare for a third wave, an influx of patients whose cardiovascular risk has spiked, whose chronic conditions have destabilized and whose health is in a bad way. They will need our attention, our compassion and our expertise. They will need the patient-centered care they have missed out on during these months of panic and pandemic.

As with all disasters, Black Americans will be disproportionately represented by this wave. They are in a poor position to weather it.

Keith C. Ferdinand, MD, is the Gerald S. Berenson Chair in Preventive Cardiology at the Tulane University School of Medicine and a member of Governor John Bell Edwards’ Louisiana COVID-19 Health Equity Task Force. He is a member of the Alliance for Patient Access.