Over the last few decades, improved body armor has helped protect America’s men and women in uniform from fatal complications such as those from close-proximity blasts. They’re surviving. They’re returning home to their spouses, partners, parents and children.

Over the last few decades, improved body armor has helped protect America’s men and women in uniform from fatal complications such as those from close-proximity blasts. They’re surviving. They’re returning home to their spouses, partners, parents and children.

But many still have wounds – some visible, some invisible.

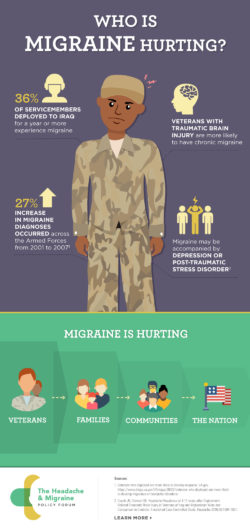

Active duty soldiers continue to have concussions at an incredibly high rate. Headache is the most common and often disabling consequence, but it can also be a sign of other troubles. Sleep disturbances, personality changes, irritability and anger also emerge, requiring multiple types of treatments. For those with migraine, peak years are 25-55 years of age, at the prime of life.

At James R. Couch, MD’s veteran’s health clinic at the Oklahoma University Health Sciences Center, headache disorders are common diagnoses. Dr. Couch recently studied veterans who had served in Iraq or Afghanistan in the previous two to 11 years. His research revealed that, of veterans who had incurred a traumatic brain injury:

– 6% had severe or disabling headaches

– Headache days averaged 10 to 14 per month

– 9% had chronic daily headaches, defined as 15 headache days or more per month.

Veterans seldom experience headache alone. More often, they battle a scattered assortment of symptoms, disturbing memories and pain – especially back pain. Post-traumatic stress disorder and depression are also common.

For these heroes, headache can be a symptom of traumatic brain injury, often occurring alongside dizziness and problems with memory and thinking. Patients describe leaving Post-It notes to remind themselves to complete daily tasks or where to find household essentials. Some find that they cannot watch movies with their families; they must leave the living room to escape the noise and fast-paced visuals. Leisure activities become less feasible, and quality of life wanes.

Treating these men and women is a bit like assembling a jigsaw puzzle, all the while trying to overcome certain anomalies. It is interesting that sometimes there is no correlation between the severity of a servicemember or veteran’s injury and the severity of his or her headache. For some patients, symptoms don’t fully materialize until years after their service has ended. “Treating active duty soldiers is a privilege,” explains Alan Finkel, MD, of the Intrepid Spirit concussion care clinic at Fort Bragg, North Carolina, “but it’s also a challenge.”

Headache and its common comorbidities, depression and PTSD, impact all levels of the military and of veterans’ lives. Though headache may not be bad enough to confine patients to bed, it does make it difficult to remain employed. Frequent absences or periods of diminished work efficiency can undermine career advancement.

Balance problems and dizziness can be uncomfortable, embarrassing or even debilitating. Veterans may be overwhelmed in an environment with harsh lights or loud sounds. Their memory may falter. Some experience exertional headaches when they exercise, making training to return to duty or life’s activities a constant and daily challenge.

And almost always, their relationships suffer. Spouses say: You’re not the same guy – or girl – I married. Most veterans will acknowledge that it’s true. They just don’t know how to fix it.

The Department of Veterans Affairs is working to meet these veterans’ needs. It’s developing concussion clinics and targeted programs, such as Operation New Dawn, which screens for traumatic brain injury. It’s enlisting headache specialists as needed. Meanwhile, new drugs known as CGRP inhibitors offer a promising means of not just treating but preventing migraine attacks. But the VA simply doesn’t have enough people to care for all our veterans, especially those with headache, mental health needs and traumatic brain injury.

This Veterans Day, it’s important to say “thank you” to the men and women who’ve put themselves in harm’s way. But let’s show them our thanks, too – by ensuring better access and better treatment for the injuries they sustain in service to our country.

###

Alan Finkel, MD, is a neurologist in Durham, North Carolina and a member of the Alliance for Patient Access. He treats veterans at Fort Bragg, North Carolina. James R. Couch, MD, is a professor of neurology at the Oklahoma University Health Sciences Center in Oklahoma City.